STUDENT REVIEW: THE BOY AND THE HERON

by Ben Packer (University of Sussex)

Reviewed as part of CINECITY The Brighton Film Festival – Duke of York’s 12 Nov 23.

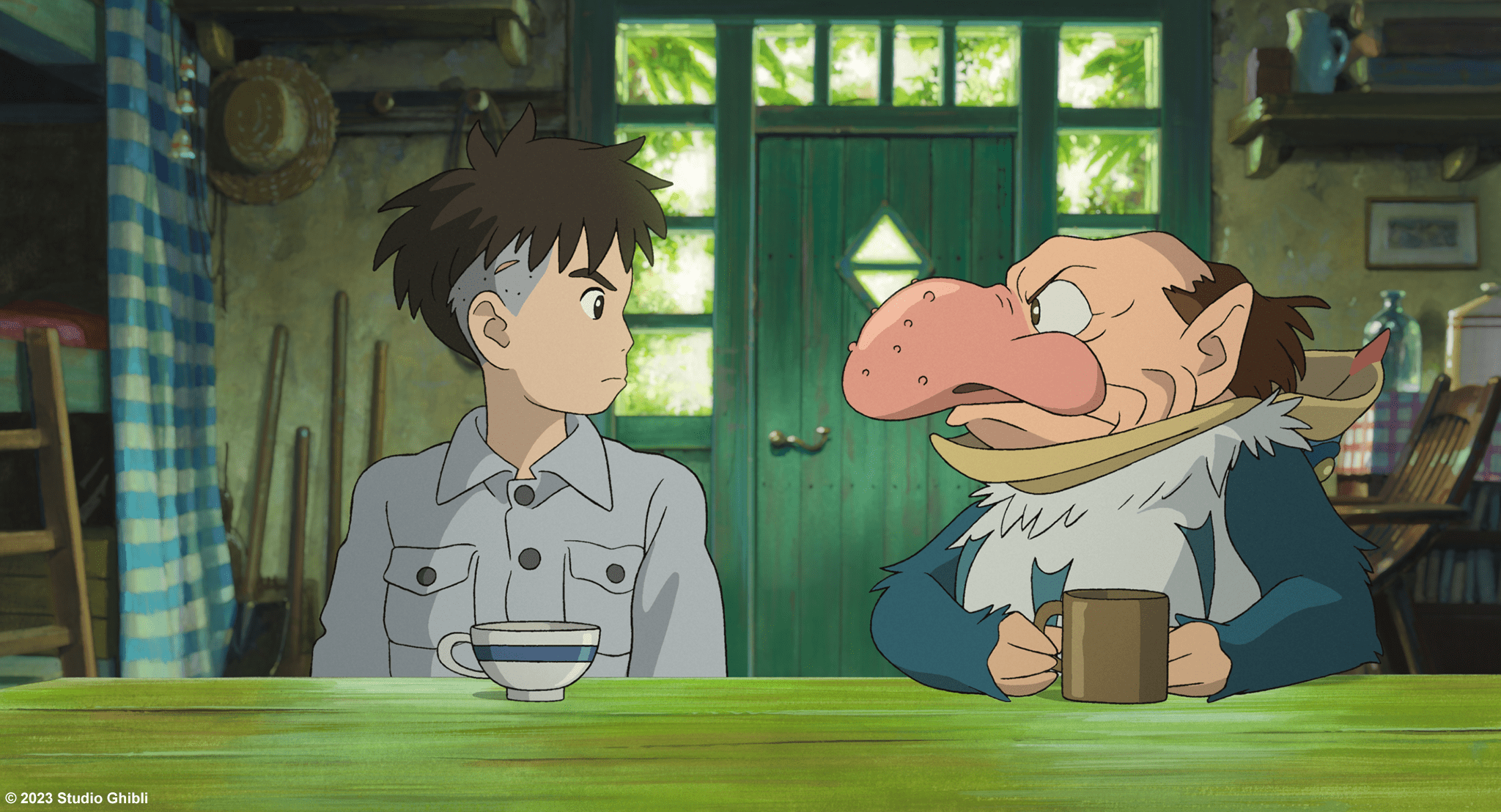

If one thing is for certain about the latest film from Studio Ghibli and supposedly last from Hayao Miyazaki, it is that The Boy and the Heron is certainly a fitting send off for the legendary director, achieving majestic world building with timeless animation in order to tackle some of his most personal, existential themes.

A pattern in Miyazaki’s filmography, present here, is crafting a child’s perspective, frequently one dealing with an almost unfathomable loss, and using the limitlessness of fantasy for the child, in this case Mahito, to process those larger-than-life emotions. Thanks to his seemingly endless imagination, producing meticulously built worlds and creatures, Miyazaki always possesses the ability to revert you back to a child, making for a magical experience whether you are an adult nostalgic for that curious, innocent age, or a child immersed in discovery every day. The overwhelming, fantastical journey the film sweeps you up in gives us a window into Mahito’s feelings as he is forced to adapt to new surroundings and accept a life without his mother. I found there to be less focus on Mahito himself as a character, with more of the emotion coming from the concepts he and I, as the viewer, were plunged into, rather than empathising directly with this strong-minded, grief-stricken protagonist.

The emotional context of the premise allows Miyazaki to do what he does best: controlled chaos. There is an unpredictability, even what may seem like a randomness, as what was initially a simple tale escalates, morphing into something more and more bizarre and surreal, building to a final act that climaxes in emotion and narrative scale. This climax allowed for Miyazaki to reach me on an intimate, personal level, reflecting on his legacy as he faces the completion of it and inevitably delving into existential themes of death and preserving what he has built beyond his life. Miyazaki’s visual storytelling prowess shines through not just through the animation, but the simple ideas used to express these huge yet delicate themes, with well-placed minimalism that shares his fears on a universally understandable level and stands out among the deliberately overwhelming chaos.

Whenever I watch a Studio Ghibli film, if I was none the wiser, I would never know when the film had been released, and that is part of the magic of their genuinely timeless style. Their hand-drawn animation does not require any kind of evolution, giving the entire body of work a feeling of harmony and immortality, as if truly a living, breathing world separate from our reality, making the themes of legacy all the more potent as it urges you to reflect. Something so beautiful about this film is that it encapsulates Miyazaki and all he has achieved, while never leaning into arrogance or pretentiousness, as well as expressing the existential, unavoidable helplessness that comes from everything having an end.

The Boy and the Heron epitomises everything Miyazaki: his visual style, storytelling techniques and endless originality he puts to screen like a magician. If this really is to be his final film, it is not only appropriate, but a moving acknowledgment of all he has achieved and an examination of coming to the end, whether that be completing a legacy or even a life.